This analysis was prepared for the Vanuatu Business Review. It appeared in this month’s edition of the magazine.

“…graduation is a waypoint, not an endpoint” – LDC Graduation Strategy Report

It is tempting to talk about Vanuatu’s twice-delayed graduation from Least Developed Country status as an achievement.

It’s more useful to see it as a landmark on the long road to prosperity.

That landmark doesn’t simply disappear once we’ve passed it. It will remain visible in our rear-view mirror for some time to come. Vanuatu’s LDC Graduation Strategy report says it could be useful to continue measuring our progress against the old metrics for some time yet.

But what does graduation actually mean?

Measuring development

The idea of a list of Least Developed Countries arose in the 1960s. It was intended to be a special category for countries with the greatest social and economic development challenges and the least achievements so far.

The list was adopted by the UN in 1971. Within a decade, 31 countries had been rated as LDCs. Vanuatu joined the Least Developed Country club in 1985.

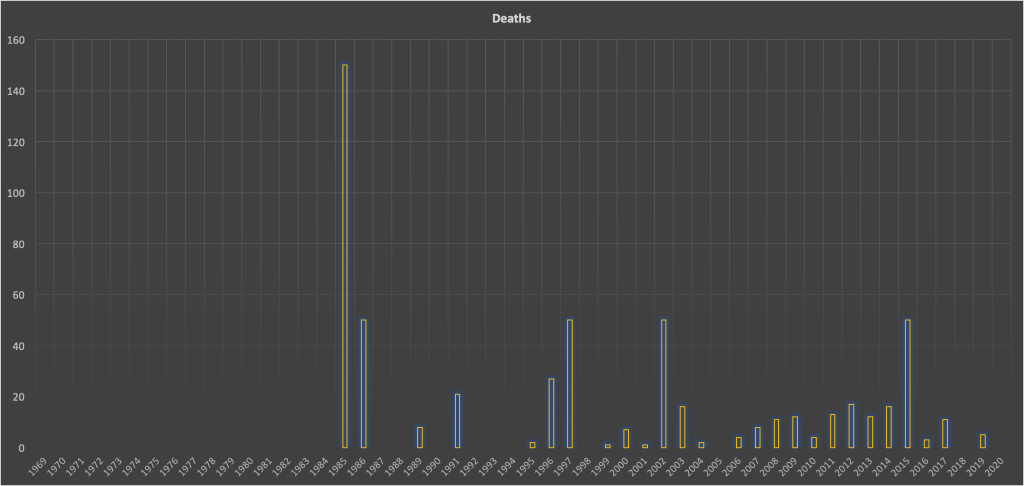

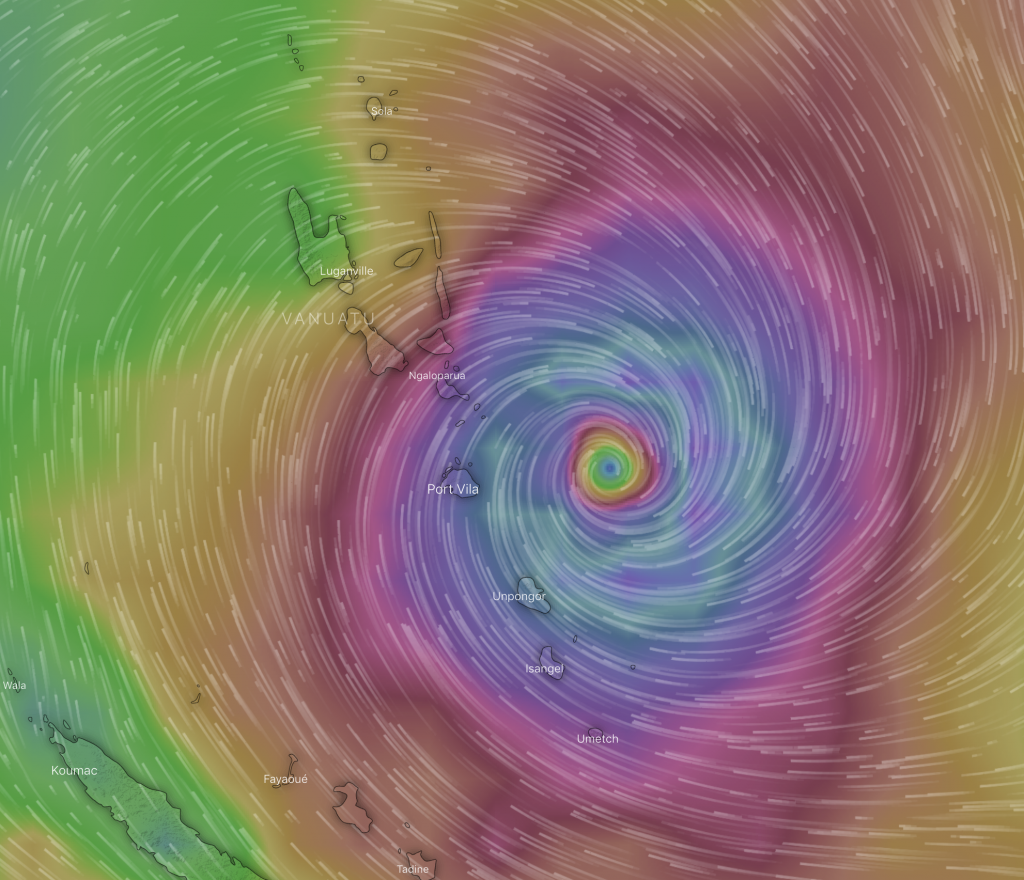

Vanuatu is only the sixth nation to have graduated so far. (One LDC was de-listed when its territory was integrated into another’s.) Samoa was the first Pacific island country to graduate, in 2014. Vanuatu was originally scheduled to follow it in 2015, but the devastation of cyclone Pam led to a request to defer that moment by five years.

Solomon Islands is slated to be the next Pacific island country to graduate, in 2024.

Is it time?

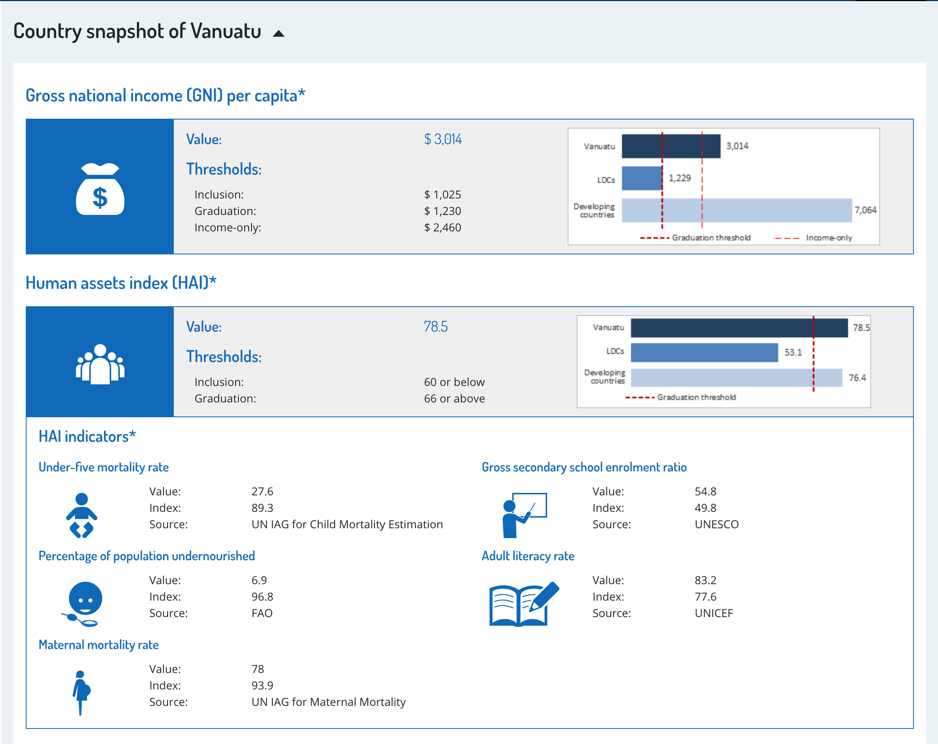

On paper at least, Vanuatu is long overdue for graduation.

When you look closer, though, the picture is less optimistic.

The LDC Graduation Strategy states that these high-level numbers hide “the reality that Vanuatu is a very unequal society, and that graduation does not reflect a large improvement in lifestyles for the majority of people, particularly those living in new urban settlements without access to land, and those living outside Port Vila and Santo.”

Ignoring the slow-rolling disaster that was 2020 for a moment, it is objectively true that Vanuatu has improved since independence. Lives, livelihoods and opportunities are far better now than they were then.

But we still have a long way to go. Assuming no major setbacks, the Graduation Strategy states “it would take over half a century to reach high income status.”

Graduation’s impacts

Most experts agree that Vanuatu’s graduation from LDC status is mostly symbolic. It’s a rite of passage more than a fundamental change.

Economist Nikunj Soni told the Business Review that the impact is effectively neutral “It is simply a change of category. Vanuatu will lose some trade preferences but nothing that is economically significant. Even in these cases there will be a five-year adjustment period, and even after that they could be continued bilaterally.”

Dan Gay agrees. He is a trade advisor who has worked with the government of Vanuatu and the United Nations. He is an expert on Least Developed Countries, and is one of the authors of our LDC Graduation Strategy.

“I don’t foresee any major changes as a result of graduation,” he said.

Three major areas are affected by LDC status, he added. Countries are expected to receive easier access to Overseas Development Aid (or ODA); they get preferential trade access; and their membership in international organisations such as the UN are subsidised.

But donor countries don’t do as much for LDCs as they’re supposed to. As a result, development aid is likely to remain unchanged. In Samoa’s case, says Dan Gay, “aid actually went up (and loans down) after graduation in 2014.”

All of our largest development partners have all signalled that there will be effectively no change to the amount or kind of assistance they’re prepared to offer. This includes the EU, ADB, Australia, New Zealand, China, France, Japan, and the USA.

One expert suggested that Vanuatu has access to more aid than it can use at this point in time, so a nominal change in financing terms would have no impact. In any case, our most important relationship—with Australia—is a bilateral one. It’s been negotiated independently of our LDC status, and change is unlikely.

Modest decreases in assistance from France and the UK were going to happen anyway, and never played a very large role in the overall aid picture anyway.

China is the only case where even marginal concerns have been raised about aid continuity, but again, Vanuatu’s development status doesn’t really come into it. The real fear here is related to geopolitical concerns that will exist regardless of how worthy we are of development assistance.

China lacks formalised criteria for aid worthiness, but that’s a symptom of their more diplomacy- and policy-driven approach to overseas assistance.

Trade not likely to change

A survey of nine international trade agreements and treaties also shows minimal impacts.

Lost revenue opportunities with the EU, for example, are likely to impact less than 1% of government revenues.

One useful lever to ensure things don’t get out of kilter overnight is a regime called the Generalised System of Preferences, or GSP. It’s different from Most Favoured Nation status, which is used between trade partners at the World Trade Organisation to ensure equality.

In a nutshell, MFN states that the tariffs you offer to your best friends should be the same you offer to me.

The GSP, meanwhile, is a regime aimed specifically at Least Developed Countries. It provides them with special access to markets that is not available to others.

When Samoa graduated, it negotiated an extension to its GSP status with China, Japan and Europe. A similar extension would protect Vanuatu from future shocks, especially for kava and noni juice exports to China.

Even if we do nothing on the trade front, though, our anaemic export levels mean that the few products and services that might face increased tariffs won’t have any large-scale effects. Individual businesses may see localised drops in profits, but they aren’t likely to prove fatal.

The most likely scenario is their products will become marginally less competitive in those export markets.

Citizenship by (actual) investment

One useful idea that from the Graduation Strategy relates to our Citizenship by Investment programmes:

“The government should also leverage any means at its disposal to persuade potential foreign players to invest in priority products. At US$150,000 plus fees, Vanuatu citizenship is among the least costly in the world, and investors are not currently obliged even to visit the country, still less invest there. Vanuatu citizenship appears to be in such demand that the government could perhaps leverage this interest by obliging buyers to invest a certain sum in priority products or geographical areas.”

The Graduation Strategy notes that the USA, EU and numerous other jurisdictions require large local investment in their programmes. If Vanuatu were to follow suit, it could have several positive side-effects.

Requiring local investment would allow the country to get more economic bang out of each citizenship sale. It would also place every new citizen under additional scrutiny. Recent financial reforms involve close monitoring of commercial activity, and this could make us more confident that all our new citizens are good citizens. It would also slow the rate at which new citizenships are granted, which would make the programme look less like a short-term bonanza and more like a viable source of long-term revenue.

All of that would make the programmes easier to defend to the EU and China, both of whom are already asking awkward questions.

Domestic production needs more emphasis

The Graduation Strategy says that “by far the biggest challenge remains building domestic production rather than securing international market access”.

It adds, “The development of productive capacity is increasingly recognised as the critical challenge for trade development in LDCs.”

Links exists between our graduation criteria and expanding productive capacity, but they’re not the key factor. Nonetheless, the strategy paper says, we should be focusing our policies on improving our ability to make goods for our own consumption. It suggests that measures should include industrial and trade policies, as well as macroeconomic measures and an active effort to enlist development support.

This would require more involvement for stakeholders: “a briefing with the Vanuatu Chamber of Commerce and Industry in October 2019 was the first time that several members reported having been given a full appraisal of the implications of graduation. If nothing else, such consultations and information sessions will reduce misinformation and avoid unnecessary complications in the run-up to December 2020 and afterwards.”

That hasn’t happened in a meaningful way. But it should, according to the government’s own document:

“The use of participatory techniques and public consultations is critical to all kinds of policymaking, not just LDC graduation. There is widespread recognition that participation brings political, legal and social benefits, improves compliance and reduces the risks of opposition. Participation can be costly but it is usually worthwhile. Stakeholders need to be kept up to date and made aware of the consequences of graduation.”

Something to celebrate?

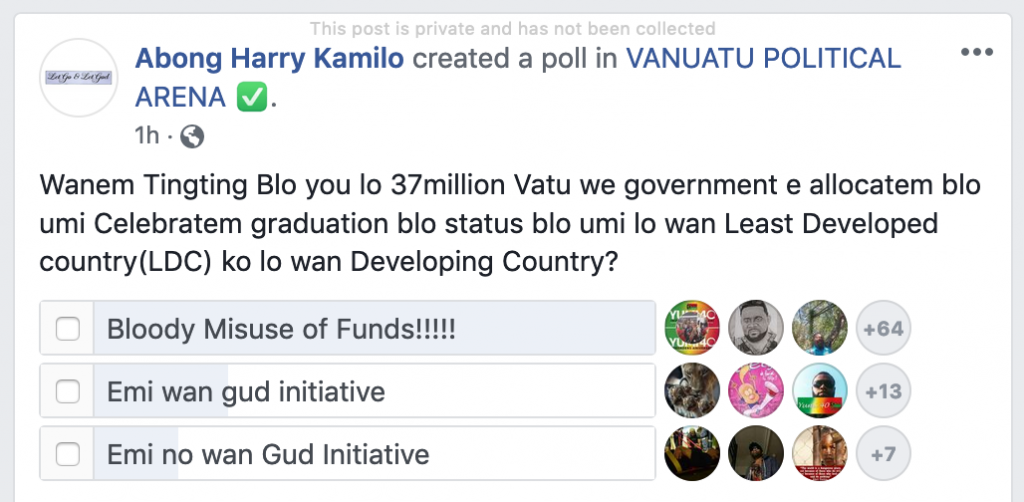

Was Vanuatu’s graduation from LDC status worth a week-long shindig costing tens of millions of vatu? Yes and no.

Vanuatu is only the sixth country in the world to graduate. In that light, it’s a model global citizen, and can rightly be held up as an example to others.

One economist with significant experience in Vanuatu argued, “Graduation is a success story for all Vanuatu. It was triggered and supported by the important work of Vanuatu’s diplomatic teams in the past two decades, but it’s an achievement that involves everyone.”

He continued, “Graduation can be a powerful marketing tool to say to the rest of the world that Vanuatu is growing and is ready to do business.”

But in light of the dire economic prospects imposed on us by the COVID crisis and the death of tourism, any celebration at all seems ill-timed.

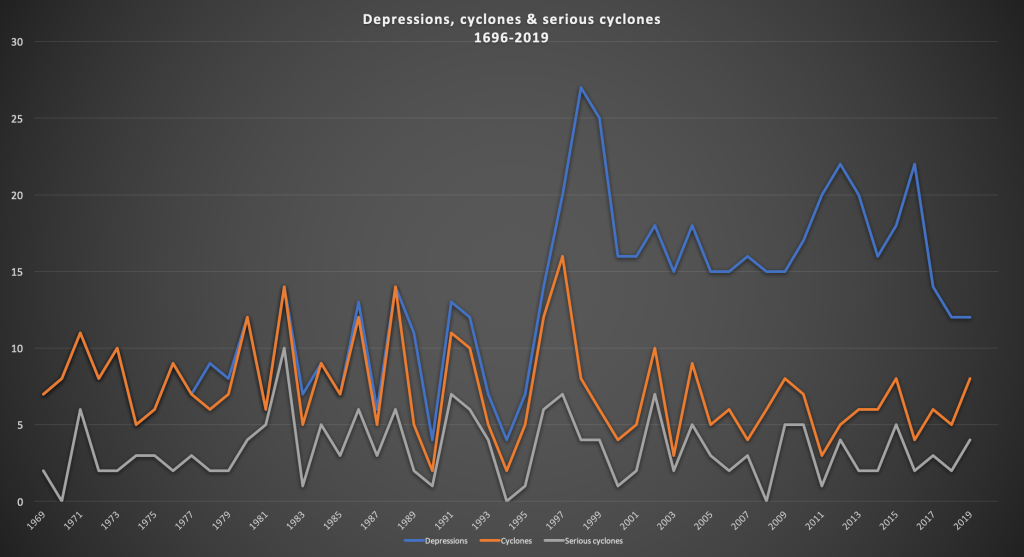

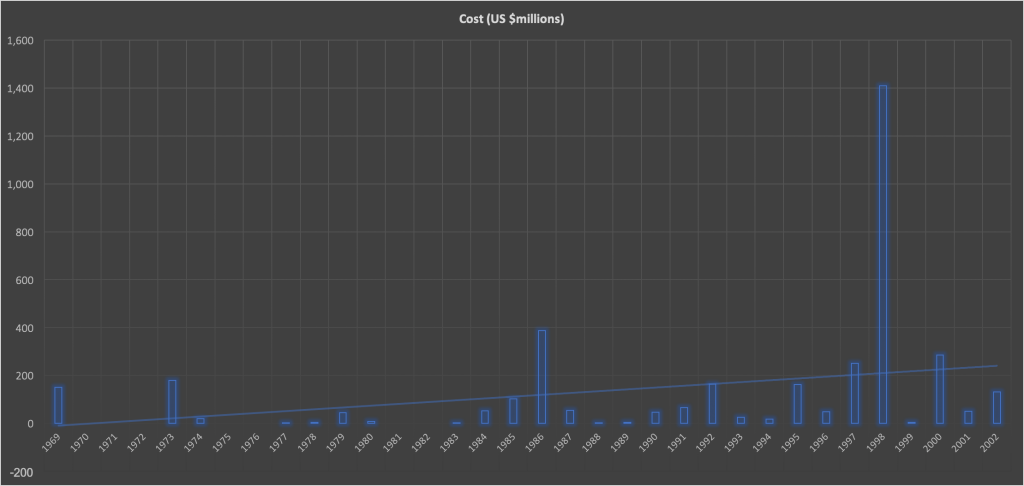

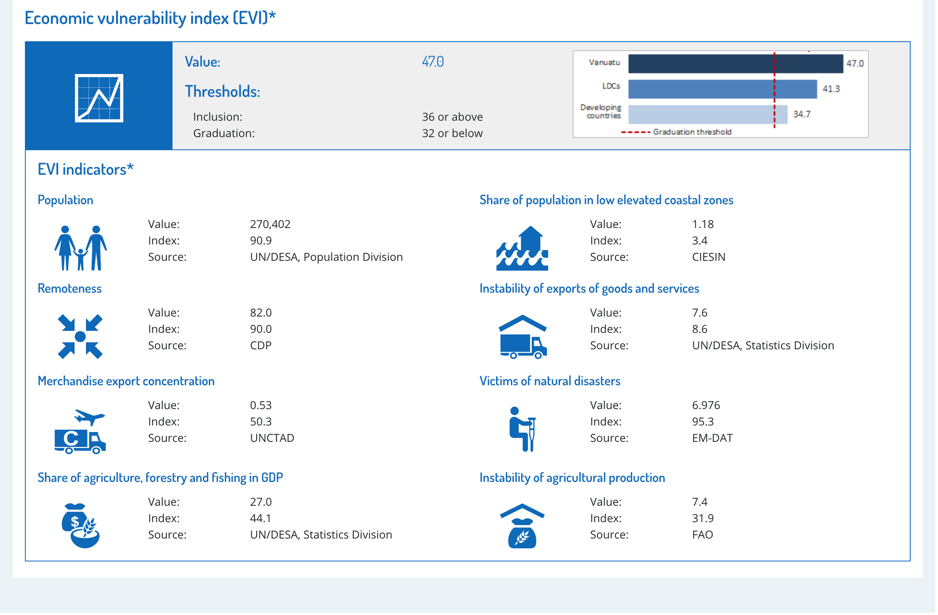

And external risks remain high, no matter what our status.

Dan Gay says, “Covid was just the latest calamity…. Peripheral nations like Vanuatu will always be exposed. Priority should be on resilience—which means… building up sources of domestic investment and financing which are not vulnerable to the vagaries of international markets.”

The list of challenges remains long, he says. The history of “attempting to expose the economy more to market incentives is a history of failure and dashed expectations. Goods trade as a percentage of GDP has gone down in Vanuatu over the last 20 years…. Foreign investment has been weak…. Trade negotiations haven’t delivered enough. Tourism, as we have seen, whilst being a valuable source of income, employment and foreign exchange, can also be very volatile”.

Nonetheless, says another economist, “It’s a positive sign to not be associated with the poorest—and in some cases worst-governed—states on the planet, and it also gives Vanuatu more weight in bodies like the UN.”

LDC graduation is like emerging from your teenage years and becoming an adult. On the face of it, you’re only a day older. Yesterday’s risks and opportunities remain. The future is no brighter or dimmer than it was.

Our responsibilities, though, are greater. And we have fewer excuses if and when we make mistakes.

If we take this moment to mature as a country, then perhaps we’ll have something to celebrate after all.

The Village Explainer is a semi-regular newsletter containing analysis and insight focusing on under-reported aspects of Pacific societies, politics and economics.