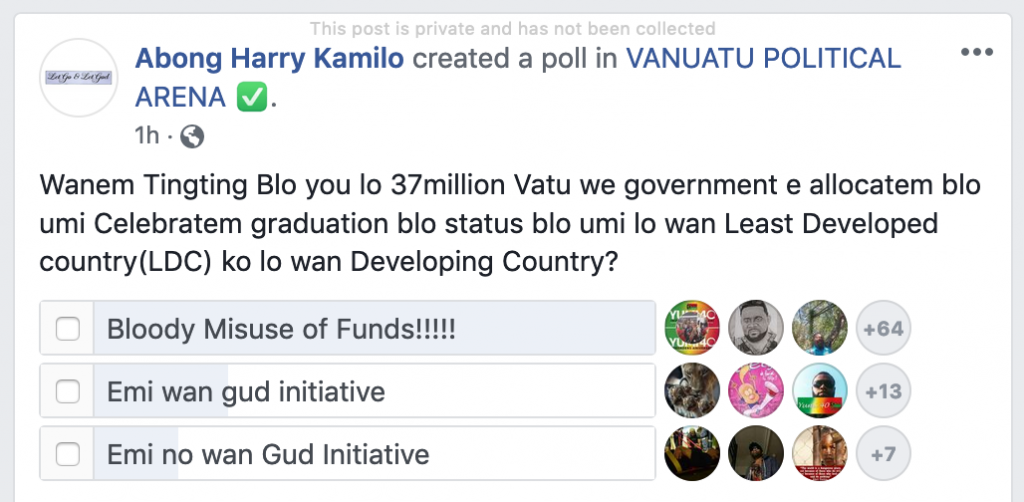

This week’s announcement that the government is spending two days and VT 37 million celebrating Vanuatu’s graduation from LDC status isn’t just tone-deaf. It’s a sad commentary on how disconnected our political elite have become from the daily reality of life and livelihood.

Today, I suspect there’s a little bit of Jonathan Edwards in all of us.

We’ve got good reasons to feel down.

The December edition of the Vanuatu Business Review includes a troubling assessment. Yes, COVID-19 and TC Harold have driven many businesses to the brink, but they were already headed in that direction before either one occurred.

For years, the rope has been tightening around the private sector’s neck. Policies designed to make life better for Ni Vanuatu are instead throttling development. The Customary Land Management Act was intended to clarify and simplify the process of deciding who had the right to lease land. It tried to shoehorn kastom and its myriad permutations that vary from village to village—let alone island to island—into a single unified system. It is unworkable.

Not a single piece of kastom land has been leased since it took effect.

Fees for work permits, visas, forms and approvals have increased beyond all reason. It now costs thousands of dollars for an investor just to reach the starting gate. The government appears to see these fees as income, not cost recovery.

Vanuatu is 107th overall in the ease of doing business rankings, but it drops another 30 places where starting a business is concerned. And it’s among the worst in the world when it comes to getting a building permit and enforcing contracts.

Businesses large and small are singled out by government officials, and subjected to orders that are sometimes unlawful and unjust.

Fairness is seeping out of the system. And without fairness, markets can’t function.

The motivation for many of these measures is commendable. Ni Vanuatu deserve a fair shake. After a century of colonial oppression, they are finally masters in their own house.

We shouldn’t be importing talent when the talent already exists here. When we do bring someone in, they should try to work themselves out of a job by providing training and assistance to local counterparts.

These are all fine ideas. Even if they weren’t, it’s not my place to prescribe policy.

I would be remiss, though, if I didn’t note the impacts.

There is a common but false assumption that if a job is created and given to an outsider, that same job can simply be handed over to a deserving Ni Vanuatu. That’s just not how things work.

If you stop a company from hiring an outsider with specific skills, you’re not forcing them to hire a Ni Vanuatu. You could be stopping them from hiring anyone at all.

Every single business owner in Vanuatu prefers to hire locally. Hiring someone from overseas costs way more than a similarly skilled Ni Vanuatu.

Local workers are a better deal for everyone. Everyone knows that already.

If a business can’t create that position, no Ni Vanuatu will ever fill it. Or be trained to fill it one day. Maybe the company won’t expand. Maybe the company won’t even get off the ground.

Maybe other jobs in the company depend on this one, and more positions evaporate.

Ni Vanuatu deserve a better living wage. But increasing it three times in 4 years, a total of 30%, only ensures fewer low-wage jobs.

Doubling severance payments for retirees creates a perverse incentive to cash-strapped companies to fire their older workers before they reach retirement age.

These measures are theoretically good, but practically disastrous. They drag down the economy, making business owners pathologically risk-averse. They’re unwilling to speak out against even the stupidest ideas, because they know they’ll be singled out if they do.

It happens all the time. I know. It happened to me.

And that’s crazy, because we’d love to help achieve those goals. As the song goes, ‘How much does it cost? / I’ll buy it!’

We really would. But difference of opinion is seen as opposition. The market for ideas just as beset as the markets of commerce.

Part of the problem is that the people who make the rules aren’t affected by them. Most MPs are career politicians. Most civil servants are career civil servants. They lack private sector experience because our tiny private sector doesn’t offer the same opportunities the public sector does.

And that’s partly because the public sector makes a living throttling the private sector.

The river of money flowing in from citizenship sales has made things worse. Politicians are no longer attentive to local businesses. They don’t need to be. They can get more support in a month from a single passport agency than a local business can offer in an entire election cycle.

And now—only now—can we begin to contemplate the damage done by two cyclones, a crisis in our aviation sector, and the death of our tourism-related economy.

Things are dire. But they wouldn’t be a lot less dire if we weren’t the most disaster-stricken country in the world.

So when the government announces that it’s splashing out nearly half a million bucks on a party to celebrate our graduation to a better economy… well, we don’t feel much like dancing.

The Village Explainer is a semi-regular newsletter containing analysis and insight focusing on under-reported aspects of Pacific societies, politics and economics.