An aviation expert has questioned the decision to fire the Air Vanuatu captain who flew ATR twin engine that veered off the runway during an emergency landing.

Air Vanuatu’s history has been blessedly unexciting. Over the last 40 years, we’ve seen only two aircraft lost, and only one of them with the loss of all hands.

So when one of our domestic flagships veered off the runway, crashing into two other small planes, we all breathed a sigh of relief that despite the damage, no one was injured and no lives were lost.

The accident investigation was conducted by Papua New Guinea’s aviation investigator, because Vanuatu lacks the capacity and expertise to do this sort of thing.

The report is troubling for a number of reasons.

Anyone who wants a detailed and insightful overview of the investigation should watch this video explainer by ATR pilot/instructor Magnar Nordal.

I spoke for over an hour to Nordal. He has been flying ATRs professionally for years, including the specific variant involved in flight 241 to Port Vila. He is a pilot/instructor who has flown in the Maldives, which is similar to Vanuatu in important respects.

What went wrong, I asked him?

Lots of things.

Engine Woes

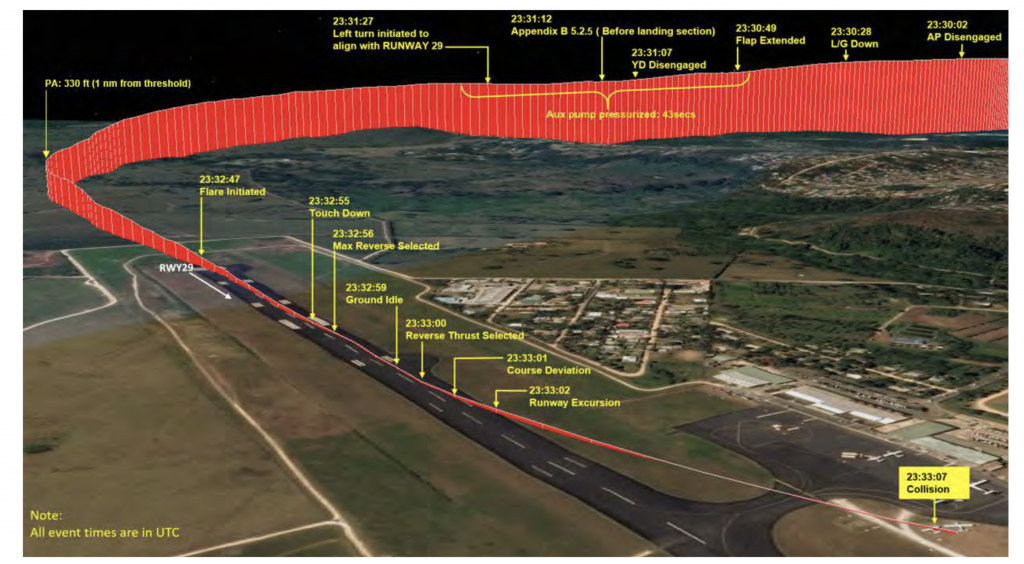

The malfunctioning of the right engine of the ATR 72-500 was what set events into motion. It failed spectacularly, with loud bangs and large volumes of smoke that quickly filled the cabin.

The engine had been sitting idle on the shelf for an extended period. It was sent to Germany for a complete refurbishment, was re-certified, and then installed on the ATR at a certified aviation facility in Fiji.

Within days, low oil pressure was noted during a flight. The fault was found, a part was replaced, and the plane was returned to service. On the next round trip, the engine unexpectedly lost oil pressure again. It was serviced again, the same part replaced, and this time a flight test was required before it was returned to service.

On the next round trip, the engine failed, apparently due to a wear on a bearing ring designed to smoothe the rotation of the engine parts. This rapidly built up friction, and ultimately resulted in numerous fractures, which released quantities of smoke into the cabin.

This frame grab from a video taken during the flight gives an indication of how thick the smoke became.

But the loss of a single engine is not an emergency. Aircraft like the ATR are designed to fly on one engine, and pilots train regularly to fly and land with a single power source. It was only when smoke entered the cabin that the pilot issued a MAYDAY to air traffic control.

Nordal agrees that was the right thing to do.

One of the first steps in the preflight checklist is to review the aircraft’s maintenance history. What would Nordal have done, given the recent maintenance issues this plane had logged?

Nordal told me he would have made a mental note, but continued with the flight. But when the engine began to make noises, that information would have been in the front of his mind.

Taking Control

When the engine started malfunctioning, the captain elected to take control of the aircraft from his copilot, who had extensive experience on the Twin Otter, but only 55 hours flying the ATR.

But following the checklists is actually the harder task. Should he have left the co-pilot in charge of flying the plane? Not necessarily. Nordal cited the popular film Sully, which tells the story of an Airbus 320 that ditched in the Hudson river when it lost both engines to bird strikes.

“Captain Sully took control of the aircraft. He even had an experienced first officer. Together they had 55,000 hours,” said Nordal.

“But in this case, you have a new first officer with very limited experience. I think the captain felt he should take control, because of the lower experience of the other pilot.”

Do we have any basis for saying that one decision would have been better than the other?

“No, I don’t think so.”

Training Inadequacies

Both flight and cabin crew were not up to date on important safety training, according to the accident report. Nordal notes that the captain’s “smoke training had expired in fact.”

Whose responsibility is that?

“You have to look at the company, how they managed the training of the crew,” he said.

Keeping good training practices is a constant challenge for small airlines.

“You always have budget constraints. You have a limited number of aircraft, with only a few pilots. Only two [ATR] aircraft, so you only have a handful of pilots. And you cannot take everybody out of production for training. You have to do them one by one. And that means you have an instructor taken out as well to do the training, and you have to repeat it many times.

“You use a lot of resources in training, so you have to do the best [you can].”

Lack of smoke training is not disqualifying, but “it should be done. It’s the responsibility of the company.”

The flight crew’s lack of training led to what Nordal suggests was a series of mistakes, each one compounding the other. They started one checklist, then interrupted it to begin another, then went back and restarted the first. As a result, a crucial detail was missed, and that resulted in the smoke problem becoming worse, and the ATR being misconfigured for landing.

“They didn’t do the complete checklist here. They rushed. They did it too fast.”

But Nordal adds that we should not be quick to judge.

“You fly thousands of hours, and never have a problem with an engine, or smoke. I have 9,000 hours total time, 5,000 on the ATR, and never had serious issues in the aircraft. So I’m very good at flying under normal conditions. That doesn’t mean I’m very good to cope with a problem like this, because I’ve never experienced it before.”

The report also indicates that the cabin crew were unaware of the smoke procedures, did not circulate in the cabin to assist passengers, and did not don breathing equipment when instructed to do so by the captain.

“I find that very serious,” said Nordal. “Very often, you think cabin crew is there for the service. But that’s secondary. The main job for them is to save the passengers. They should be properly trained in smoke procedures.”

But again, he pleads for understanding.

“There are no simulators in Vanuatu where you can practice for smoke in the cabin…. That means you do it in a classroom. You teach them, ‘do this and this and this’, but it’s very different when you say something in a classroom—that’s very different from really doing it in an aircraft.”

I asked him, would you take a plane off the ground if you knew that your cabin crew lacked the training to deal with a smoke event?

“If I knew that beforehand, I would say, ‘My cabin crew has not received proper training, so I consider I’m not fit to fly.’

“But how can I know what kind of training they have? I know they are trained by the company and the company has released them and said they are fit to fly.”

Regulatory Inadequacies

The accident report states that Civil Aviation’s oversight of Air Vanuatu’s training and certification practices was ‘inadequate’.

In aviation, the regulatory environment is designed to encourage what’s known as a Just Culture. “You’re not punished because you did a mistake. But they will ask questions if you don’t report it.”

Responsible behaviour is expected and rewarded, and provided mistakes are owned and fixed, they’re not punished. Irresponsible behaviour and hiding mistakes, on the other hand, is cause for concern.

Nonetheless, said Nordal, “there were mistakes made. But nobody died. Nobody got hurt. Which is a positive outcome.”

Captain not to Blame

“I hear that the captain has been fired.” said Nordal. “I don’t agree. Because I am sure that the captain will never make that mistake again. He learned something important here. That alone should not qualify to fire the pilot.

“I’ve seen in other cultures how they fire the pilot for tiny, tiny mistakes. That caused other pilots to be afraid. They are scared of making mistakes. And when you focus on not making mistakes, guess what happens?”

He continued, “I question their decision to fire the captain. Unless there was something else we don’t know about. I think it’s not fair to blame the captain alone, because as the report says, his smoke training was overdue. That goes back to the company. It’s not only one [person] responsible here. The captain made the decisions, but behind him you have a culture and an organisation.”

Many have already called for the captain of flight AV241 to be commended, rather than have his career called into question.

But as the accident report states bluntly at the beginning: Readers should note that the information in AIC reports and recommendations is provided to promote aviation safety. In no case is it intended to imply blame or liability.

The most worrying aspect of this entire episode is that the accident report was not circulated at all in Vanuatu, nor was it discussed. As Nordal underlined repeatedly, if you hide your mistakes, and spend your time worrying about people finding out about them, you not only don’t improve, you create fertile ground to make more of them.

Simply firing the pilot and sweeping the underlying contributing factors under the carpet is a recipe for further disaster. If Air Vanuatu wants to grow as an airline, it has to recognise its deficiencies, own them, and treat them responsibly.

Who would fly on an airline if they thought it was hiding critical safety information from them? The only way we can build confidence is through robust regulatory oversight, and complete transparency when mistakes do happen. Because they inevitably will. And if we don’t learn from them, we are sure to make more.

The Village Explainer is a semi-regular series of analysis and insight focusing on under-reported aspects of Pacific societies, politics and economics.