Tucked away in the corner of an otherwise nondescript building in Paray bay in Port Vila is an office that quietly buzzes with activity. Fisheries Compliance Manager William Naviti and his team operate a 24/7/365 monitoring service that tracks all fishing vessel activity in Vanuatu’s waters, as well as keeping tabs on Vanuatu-flagged fishing boats wherever they are on the planet.

In 2014, approximately 50 long-liner vessels caught an estimated 6,636 tonnes of tuna and related by-catch, generating nearly 800 million vatu in value, including roughly 90 million vatu in government revenue.

Albacore represents the lion’s share of the catch, over 70% in all. Another 15% is Yellowfin tuna, with a further 2% or so belonging to Bigeye. The remainder is by-catch—game fish species whose feeding habits are similar to tuna.

All fishing vessels licensed to operate in Vanuatu’s Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ, are required to carry radio beacons which send a constant signal to a satellite-based system that tracks where they are as well as what they’re doing.

Sophisticated logic can differentiate between a ship cruising to its chosen fishing grounds, and one that is actively fishing. It can spot when two ships meet and if they attempt to transfer catch, crew or contraband.

The system, developed by the Forum Fisheries Agency, is an international tracking service. This is critical, because it means that dodgy operations can no longer go jurisdiction-hopping—jumping from one country to another one step ahead of enforcement agencies.

A 50-inch high definition display shows every vessel in or near Vanuatu’s waters, and a coloured flag indicates their status. Each vessel’s path over the last 24 hours is run in a loop, with current position constantly updated. The result image is of a cloud of tiny green markers repeatedly zipping north and south like dragonflies across a pond.

In their midst, a couple of yellow-flagged vessels are visible. These are ships that are noteworthy for any reason: they’ve recently approached other vessels, or their license status is unverified, or similar. Not a problem necessarily, but worth watching.

On top of all this float one or two icons glaring angry red. One such has an outstanding license infraction in Solomon Islands. Another is a false alarm; the FFA hasn’t received the ship’s license information yet due to delays on the Vanuatu side of things, so it thinks the ship is operating illegally.

The alert in this case is unneeded, but it’s a good example of how closely we are able to watch those who take fish from our waters. There have been a number of fines laid in the last year, mostly brought about by failures to report activity.

Fisheries staff declined to discuss specifics, but confirmed that there have also been successful prosecutions in recent years.

But we could be doing more. Officials pointed out that critical components of the information flow are still being handled on paper, and often by third parties. Issues of timeliness and trust are fundamental when the health of the national fishery is concerned.

One staff member suggested that if Vanuatu-licensed vessels were required to offload in Port Vila, we could have much finer-grained control over the catches taken by long-liners.

The benefits, they said, would be twofold. First, we could require Ni Vanuatu observers on every single vessel. This would do a lot to improve transhipment and responsible by-catch handling. Second, it would allow detailed statistics to be gathered concerning fish size, weight and quality. As a bonus, it would also create hundreds of jobs.

The Fisheries staff we met with last week were clearly proud of the work they were doing. They showed off their monitoring systems, records and related materials with confidence. They were also quick to note that their office not only pays for itself, it is one of the larger sources of government revenue.

But technology, as ever, takes as well as it gives. More than ever, nations all around the Pacific are looking to the oceans to feed their growing populations. Increasing long-liner activity is putting intense—some say unsustainable—pressure on tuna stocks.

Pacific island countries are working more and more closely together, increasing the sophistication of their management and monitoring efforts. But they’re fighting a rising tide.

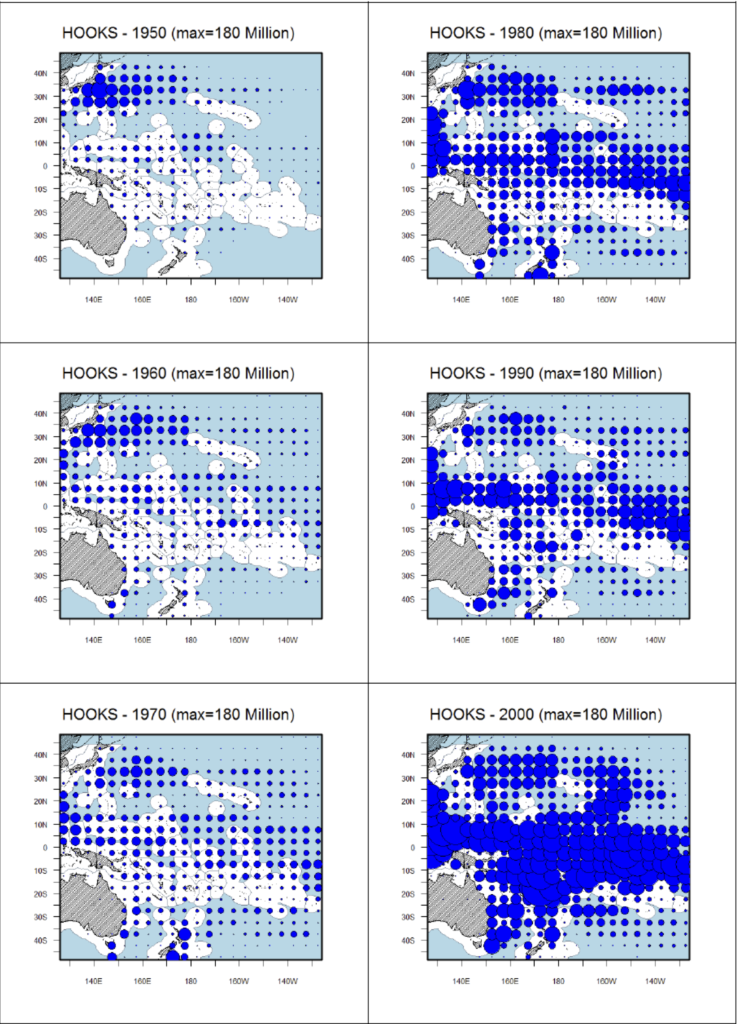

The number of long-liner hooks deployed has increased to an astonishing degree in recent years. Source: Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission

Estimated rates of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing—called IUU by industry watchers—are lower in the tuna fisheries than, for example, the Canadian cod fishery, which was savaged by unregulated trawlers. Things got so bad that Canadian navy vessels were deployed to warn off illegal ships. It was too little, too late. The commercial cod fishery collapsed, damaging the economy of much of the East coast of Canada.

What can Vanuatu do if it comes across IUU activity in its waters? Clearly, relying on Tukoro is not a pleasant prospect. Thanks to closer cooperation between nations, a ship engaging in questionable activity can be tracked all the way to its next port of call, subjected to additional scrutiny and, if necessary, prosecuted, fined or otherwise penalised.

In principle at least, things are better now than they’ve ever been.

And yet, Yellowfin and Bigeye numbers continue to dwindle. Elsewhere in the Pacific, Bluefin tuna are nearly commercially extinct. The population is reduced to a mere 2.4% of its ‘pre-fishing’ level, according to a recent report, down from an already disastrous 4% in 2013.

In 2015, the US government listed Yellowfin tuna as a species in particular peril because of IUU. That’s a little rich, according to some. Industry watchers agree that it’s the big players who are to blame.

Quoted in the Guardian newspaper, Amanda Nickson of the Pew Charitable Trust’s tuna conservation initiative said, “The big nations are the disappointing ones, given that they’ve refused to take cuts in their quota. All the scientific advice shows that tuna is being overfished.”

One global study estimated the value of illegal fishing in the Western Central Pacific region back in 2000-2003 to be between US$707 million and 1.5 billion annually. That’s over a third of the total taken.

What’s sauce for the gander is sauce for the goose. Technology allows us to watch ships in real time. It also makes it easier for fishing operations to operate on an industrial scale, and with vastly greater focus and efficiency.

One marine biologist interviewed for this article said, “the issue at hand is not about if they know where the vessels are and what are they doing. But what is the competitive advantage that a company now would have that did not have 5 years ago?”

Experts also questioned whether by-catch was being handled as responsibly—and as honestly—as it should. Some went so far as to suggest that shark fin harvesting was one of the motivations driving the intensified interest in expanding Vanuatu’s fishery.

Technology giveth; and technology taketh away. With luck and perspicacity, Vanuatu can sustain a profitable and well-managed commercial fishery. But the stakes are high. If we lose our edge, we stand to kill the so-called Blue Economy.