The pandemic is global. Why isn’t the response?

When scarcity butts up against the public good, tears are guaranteed. This year—and for years to come, it seems—COVID-19 will provide ample opportunity to cry.

First, a word of congratulations to the cohorts of ideologues who spent decades grinding the United Nations down from a place to grapple with global crises to an underfunded, slothful, toothless show dog. Great job, gang. It’s not like we needed it.

What we have instead is a creative response to vaccination in a world where governments don’t want to cooperate, let alone play by the same rules. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance was cobbled together by dozens of different stakeholders about 20 years ago to deal with something that we’ve always known is a problem: eradicating communicable disease in a world with wildly disparate levels of wealth and health.

The good news is that it was a relatively simple (albeit herculean) job to refocus GAVI on COVID-19 and to form COVAX, the global initiative designed to centralise vaccine acquisition, coordinate its delivery and reduce costs for everyone involved.

And it would be working well, if developed countries hadn’t jumped the queue. Sidelining their own contributions to COVAX, 16% of the world’s population has removed 70% of global vaccine production from control of the global consortium.

The already confusing and complex global supply chain has effectively been corralled by the moneyed nations who are intent on vaccinating themselves first.

That’s crazy, when you think about it.

It’s not crazy at first, though. I mean, it’s their vaccine. They can do what they like with it. And a lot of the money is theirs too, so ditto. And they were elected (or self-selected) to protect the interests of their own people. So… yeah. Ok.

Crying about basic injustice is a legitimate response. The fact that people are willing to shove others out of the way in order to secure a place on the first lifeboat out is lamentable, and not very cool. I seem to recall a bit of confusion about that in Titanic.

But let’s be honest. Fairness is a powerful argument, but not a compelling one.

The calculus that should be driving a coordinated global vaccination effort is the desire to see this thing ended decisively and quickly. A globally coordinated response isn’t just the right thing to do. It’s the best thing to do.

The longer the disease lingers in locales with poor health care services and large populations of people facing multiple concurrent health challenges, the more likely it is to mutate and re-emerge.

In short: If you shoot the first zombie, The Walking Dead never gets past the pilot. If you don’t, you… well, you get the show as premised.

A policy paper published a few days ago by The Lancet lays it all out. It recognises the near-miraculous speed with which the first vaccines have been produced, but warns that if production, pricing and allocation aren’t better coordinated, we could end up drowning in a rush to the lifeboats.

Scaling up production to meet global demand is a monumental challenge.14, 15 Before this pandemic, there were no existing networks of contract manufacturers for several of the leading vaccine candidates that feature novel technologies, including those relying on mRNA delivery platforms. Additionally, the volume of vaccines that is needed places pressure on global supply chains for inputs, such as glass vials, syringes, and stabilising agents.

The production of COVID-19 vaccines is limited by the highly concentrated state of global vaccine manufacturing capacity,16 and the relationships established between lead developers and contract manufacturers. A successful solution to the production bottleneck would probably require widespread technology transfer to enable the expansion of manufacturing capacity.

And yet, there’s no appreciable effort ongoing at the moment to move production into the public domain. Cooperative vaccine deals such as that negotiated by the Quad are good, but they’re just working around regional and strategic rivalries that the UN was specifically designed to circumvent.

Yes, millions will benefit from this, and that’s an unadulterated Good Thing. But it’s too small.

The Lancet makes it clear that self-interest is driving up prices for everyone, and contributing to supply shortages that virtually assure a more protracted fight against the vaccine for everyone. Looming over all of this is the spectre of COVID becoming a long-term affliction of the human species, slowing commerce and travel for decades to come, increasing distrust and instability, and punishing the poor.

Delays cost everyone. Eric Feigl-Ding is an epidemiologist with the Federation of American Scientists. He argues, “Delaying the vaccine is a terrible choice. If you were to choose, just take whatever is available because every day for 100,000 vaccinations that are delayed by just one day 15 people will die.”

That’s in the USA. The numbers for Papua New Guinea don’t bear contemplating.

We can’t say we weren’t warned. We knew that if—or more honestly, when—COVID-19 broke out into the community in PNG, it would create a dire threat. One that nobody is equipped to cope with.

Today’s announcement of an urgent effort to guarantee enough vaccines for 20% of Papua New Guineans sound good. Better than the next-to-nothing they’ve got right now, anyway. But 20% of the population in the first year has been the COVAX goal from the start.

That number was based more on market factors than epidemiology. It’s saddening that it takes a crisis of these proportions to raise even the prospect of meeting it.

We now know that vaccines don’t just protect a person from the virus, they also reduce transmission rates vastly, so its possible effective herd immunity may be reached a little shy of the 60% number that’s been bandied about since the beginning of the pandemic.

But here’s the catch: That number only works within discrete populations. We are content to divide ourselves along national boundaries for the moment, so that’s how eradication is going to manifest. The virus will be reduced significantly at first, perhaps even to vanishingly small rates in Europe, North America and large swathes of Asia.

But it only stays eradicated as long as the barriers remain.

And in pockets of the Pacific, in sub-Saharan Africa, remoter parts of Asia and South America, the virus will cling to humanity like a leech, mutating, waiting.

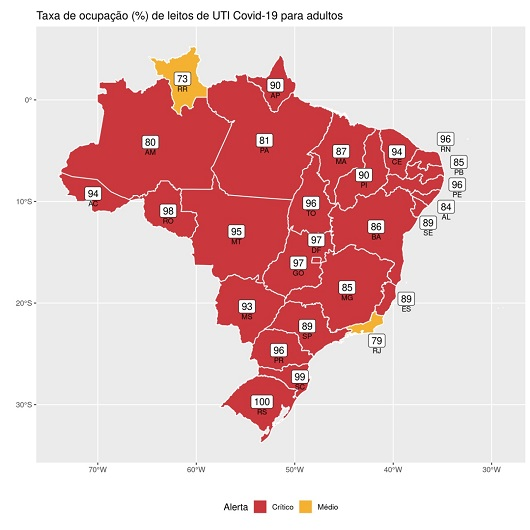

This is Brasil today:

PNG is even less equipped to cope with a runaway virus than Brasil is. We’ve known these were the stakes for a year. It is likely already too late. To his credit, James Marape has been pragmatic about this from the start. Some would say fatalistic.

Some would say that fatalism is an appropriate response.

A million vaccines for PNG isn’t nearly enough. If we’re being fair, the same can be said of every number, for every nation, until the virus is eradicated.

But the way things are going right now, it’s not clear that global eradication going to happen. Because there is no actual global eradication effort. And the odds of success are being driven down right now by wealthy nations getting their own self-interest exactly backwards, because they think there’s a difference between national interest and global interest.

Where they see rivalries, the virus sees opportunities.

COVAX is being undercut by queue jumpers. According to the Lancet, it is facing a multi-billion dollar shortfall, and it’s being outbid by developed nations. It has no long-term funding, and is ill-equipped to build any formal frameworks and supply chains in a marketplace that isn’t just short of vaccines, but also needles, vials, gloves, masks, protective gear—in short, every single thing it needs.

The Lancet policy paper argues convincingly for a global approach to vaccination. But there’s a difference between convincing and compelling. What we need now is the latter. We need world leaders to realise that they’re not protecting themselves if they don’t protect us all.

This is a critical moment in human history, and thus far, we’ve reacted with historic rapidity. But there’s a good chance that we won’t succeed unless we put our differences aside and tackle this global challenge on a truly global scale.